With Ukraine moving towards greater European integration, the country’s regional institutions require better coordination, stronger financial backing and capacity-building support if they are to fulfil their potential.

Natalia Haletska

This blog post is also published in #RebuildUkraine series with the UiA Democracy in Action Blog.

Ukraine must implement an array of reforms along the road to becoming an EU member state, some of which will have to be realised at the regional (oblast) level. Currently, the country’s regional institutions face a number of challenges that will need to be addressed if they are to become sufficiently robust actors in Ukraine’s bottom-up European integration. Based on the author’s personal insights as a member of Lviv Regional Council, this blog offers some insights into how the regions’ role might be strengthened in this regard.

First steps towards bottom-up European integration

To understand the source of the current challenges, one needs to look at how Ukraine’s regions have participated in the European integration process thus far. The necessity of engaging regions as separate players was first defined in the Strategy of the European Integration of Ukraine, adopted in 1998. Subsequently, the Ukrainian parliament adopted the 2004 ‘On Cross-Border Cooperation’ law, which defines the frameworks under which regions and communities can participate in EU cross-border cooperation programmes.

Building on the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement – which was signed in 2014 and came into force in 2017 – Ukraine’s Law as of 2015 ‘On Foundations of State Regional Policy’ law added an additional framework for engaging regions in the European integration process. This included the regional development agencies each of the country’s regions is supposed to possess. At the same time, regional executive bodies – such as regional state administrations – attempted to issue regulations on implementing European integrations steps, although these were generally declaratory rather than binding.

More recently, local self-government bodies have started to participate in the EU cross-border programmes with increased enthusiasm, even providing financial resources from their own regional budgets. Having been granted EU candidate status in 2022, Ukraine has also joined several EU programmes, including LIFE (the Programme for Environment and Climate Action), Digital Europe, Creative Europe, Connecting Europe Facility and Interreg Europe, necessitating the creation of more developed, specialised institutions.

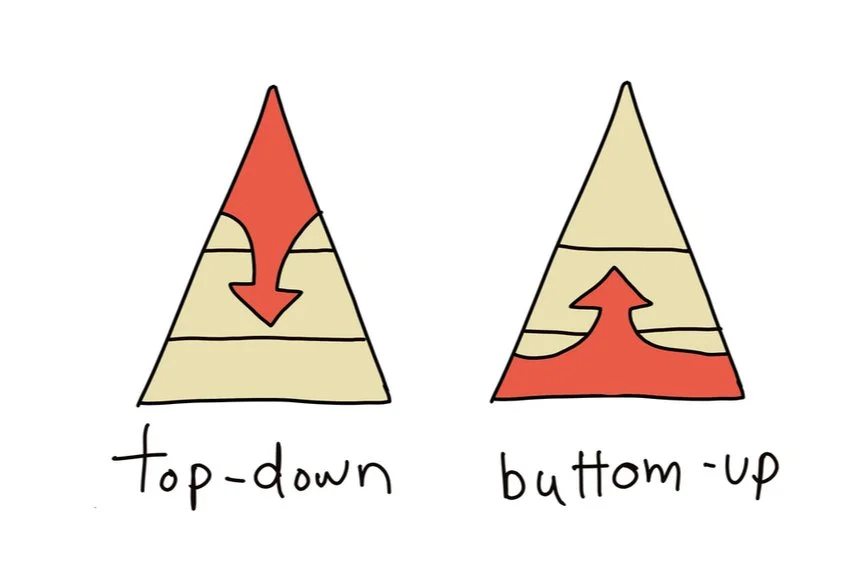

Here, it is worth noting that it has been the Ukrainian government driving the country’s engagement in EU programmes, meaning there have been few indications of bottom-up European integration in these processes.

Today, there are several regional institutions responsible for guiding Ukraine’s European integration, encompassing regional state bodies (regional state administrations before February 2022 and regional military administrations since then); local self-governing bodies (regional and local community councils, mayors); and various specialised institutions, such as the previously mentioned regional development agencies. While various non-governmental institutions (NGOs, professional associations etc.) are also involved in several of the EU programmes and projects, this blog is concerned only with state or local self-government bodies.

Regional state/military administrations: inflexible but partially active

Regional state administrations are state bodies appointed by and tasked with representing the President of Ukraine in their respective regions. They implement various state policies and process some powers delegated from the local self-government body (i.e. the regional council). Following the imposition of martial law, regional state administrations were restructured and renamed ‘regional military administrations’ after 24 February 2022.

Given their inflexible nature, these bodies are ill-suited to developing partnerships or acting as a project development and implementation office. Even so, the Lviv Regional State/Military Administration is taking steps to become more active in the area of European integration. For example, it has actively expanded its relations with neighbouring Poland by developing its own position on where border checkpoints – which are essential for promoting trade and thus the region’s economic prosperity – should be located.

Local self-government bodies: caught between increased activity and stronger constraints

Ukraine’s regional councils are responsible for developing international partnerships, as well as finding partners for their – among other institutions – hospitals, educational institutes and cultural organisations. Local community councils and mayors are, in turn, tasked with fostering cross-border partnership agreements, such as town twinning, and participating in EU programmes alongside their counterparts from other countries in the Union.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, a contradictory pattern has – judging by the author’s personal observations and discussions in Lviv region – emerged between regional councils on the one hand, and the mayors and councils of local communities on the other. While the latter have become more active in matters of EU cross-border cooperation compared to the pre-invasion period, the opposite holds true for the former.

For example, in 2017, Lviv’s Regional Council established a special programme on co-financing EU projects, thereby allowing local communities and communal institutions to participate in larger projects. The subsequent halt in such activity stems from legislative changes transferring budgetary and other powers to the regional military administrations after February 2022. As a consequence, the majority of functions of the regional councils are now performed by the military administrations. This has deprived the Lviv Regional Council of the financial resources necessary for the co-financing programme.

The shift in powers outlined above has negatively impacted the speed of Ukraine’s European integration, as European regions can no longer find Ukrainian counterparts with the necessary scope of powers. Regional military administrations cannot fulfil this role, as all their activities are coordinated and approved by the Office of the President of Ukraine. Due to this top-down nature, they are not self-government bodies and so lack the democratic legitimacy conferred on such bodies. As a consequence, neither the regional state/military administrations themselves nor the local self-government bodies within their jurisdictions can be considered bottom-up drivers of European integration.

Specialised institutions as regional integration champions

Against the above backdrop, the ‘specialised institutions’ – with some exceptions – emerge as the most suitable means of driving European integration. These institutions include the European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC), regional development agencies, regional associations of local self-government bodies, and the local self-government bodies’ representative offices abroad.

The EGTCs allow for much faster project development and implementation, as such groupings are based on EU law and created for a specific purpose. The first grouping in Ukraine, Tysa, was created in 2015 between Zakarpattya region and a partner region in Hungary. This example has not, however, been followed by many, despite changes to the ‘On Cross-Border Cooperation’ law that make the creation of these institutions less problematic. While some preparations have been made in the Lviv region for the establishment of further EGTCs, progress has been painfully slow. Here, a dedicated programme supporting the formation and development of such institutions could help speed up the process.

Prior to the full-scale invasion by Russia, regional associations of local self-government bodies – the legal status and powers of which are defined by the ‘On Local Self-Government Associations’ law – were very active in the area of European integration. In 2013, one such association, Dnister, opened a representative office in Brussels, while in Lviv region, Euroregion Karpaty – Ukraine has been developing and implementing projects across four of the country’s regions.

In the wake of the invasion, however, and more generally following the creation of the regional development agencies, these associations have become less active. One lesson that may be drawn from this concerns the risk of creating institutions with similar functions, as this can spark unnecessary competition. To address this, the competences of the various institutions should be divided up on the basis of project-level priorities in areas such as digitalisation, culture and environment/climate change.

Regional development agencies can be established cooperatively by a regional state/military administration and its regional council counterpart, although other founding parties may also be involved, such as universities or NGOs. In 2019–2022, efforts were made to transform the regional development agencies into regional offices of European integration. This did not, however, find much success due to the lack of a defined aim.

The fundamental aim underlying the regional development agencies is to establish apolitical bodies capable of acting as a project development and management office for the entire region. This includes communicating with foreign donors and initiating relevant projects and programmes. According to the 2022 Report of the Ministry of Infrastructure on the Activities of Agencies, this aim has yet to be achieved. Thus, the Ukrainian government is currently seeking an appropriate model that will enable the regional development agencies to fulfil their potential.

Drawing lessons from the Lviv’s regional development agency

The history of the regional development agency’s establishment in Lviv region is somewhat complicated. The initial agency created in 2019 only had a single founder – Lviv Regional State Administration – which meant it did not comply with legislation. At the same time, the association of local self-government bodies was active in Lviv region, making it extremely difficult to create a competitor.

Nevertheless, the Regional Development Agency of Lviv Region was finally created in 2023 by the appropriate founders (i.e. Lviv Regional Council and Lviv Regional Military Administration). The author actively participated in its creation in 2023, allowing for the drawing of some important conclusions in this blog.

Upon coming into existence, a regional development agency is fully dependent on regional resources (office, regional funds), as there are no funds allocated in the state budget. Thus, the appointment of a director and approval of all its documents inevitably leads to a complicated process of negotiations, especially so in the period since the full-scale invasion. Such a legislative approach risks the establishment of an organisation incapable of achieving its aims due to lack of resources.

One way out of this situation is for the newly created regional development agency to swiftly secure other sources of finance, such as funds from international technical aid projects, or paid services for local communities and NGOs. It was just such an approach that was taken by the Regional Development Agency of Lviv. Doing so, however, requires preliminary investment from the regional budget, which is not always available.

Thus, another important lesson learnt is that providing for the fundamentals of a regional development agency or equivalent institution means providing the necessary funds in law.

Strengthening the regions’ role in European integration

Ukraine’s regional-level European integration efforts have developed from fragmented endeavours to much more wide-ranging, deep-rooted initiatives. Even so, more needs to be done to strengthen the regional institutions dedicated to furthering European integration.

Worthwhile paths that could be pursued in this regard include ensuring the Ukrainian regions and international donors provide the resources necessary to adequately establish these institutions; strictly defining institutional competences, thereby avoiding unnecessary duplication of responsibilities among different institutions; and putting in place an institutional support programme – possibly with funding from foreign donors – for the formation and development of relevant institutions (e.g. a ‘train the trainers’ project aimed at sharing knowledge with local communities and communal institutions such as hospitals or educational establishments).

Such improvements would help ensure the full potential of Ukraine’s regions is drawn on in the country’s pursuit of European integration.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the position of the Lviv Regional Council.

Nataliya Haletska has been teaching at the School of Law of the Ukrainian Catholic University (Lviv, Ukraine) since 2018 and has been the Head of the Master’s Programme since 2023. Nataliya is an attorney at law and leads the Lviv Regional Branch of the Ukrainian Bar Association. In 2020 she was elected as a member of a local self-government body in Ukraine, Lviv Regional Council, where she chairs the Commission for European Integration and International Cooperation. In addition, she chairs the Supervisory Board of the Lviv Agency of Regional Development. Nataliya holds a Master of Laws degree from Ivan Franko Lviv National University, Ukraine, and a Master of International Law and Economics from the University of Bern, Switzerland. In 2016 she obtained her PhD in Law. While working for one of the largest law firms in Ukraine – “Vasil Kisil and Partners” – she has been involved as a legal advisor in trade investigations and trade disputes.